BDMRR: Birth, Deaths, Marriages, Relationships, and Racism

The New Zealand parliament has been mulling a law change purportedly to benefit trans, non-binary, and intersex people by streamlining the procedure to update one's birth certificate sex marker. However, contrary to popular belief and demand, this change is constructed in a way that would be harmful to some of those people, particularly trans, non-binary, or intersex people of colour. In this post, we will see why the proposed law is racist, and how it might be rectified.

The story so far

The Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Act 1995 (BDMRRA or BDMRR Act) is a New Zealand law that governs aspects of a person's identity in the eyes of the state, including their name and sex marker (as on their birth certificate).

The Births, Deaths, Marriages, and Relationships Registration Bill (BDMRR Bill) is a government bill with proposed amendments to the Act that would allegedly make the process of updating one's sex marker more direct and easier, mainly because it would remove the need to apply to a Family Court judge for a declaration. It would rather rely on a statutory declaration process. So far, so good.

What's missing

Not obvious in the above description is the fact that the new procedure applies to eligible persons defined as those with a New Zealand birth certificate only. It would not support any overseas-born trans, non-binary, or intersex people. That means migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers. But it may also leave behind anyone who is a citizen-by-descent born outside NZ. Roughly 25-30% of the resident population of NZ is overseas-born.

At this point, you may have a number of questions. How does the proposed law define eligibility such that it leaves people behind? Why should New Zealand care about foreign documents it did not issue? Why is it racist to only target New Zealand-born people? How can we fix the bill?

Terminology

This area of the law can be quite confusing and technical. There are different categories of people, each with overlapping but different meanings: citizens, citizens-by-grant, citizens-by-descent, New Zealand-born people, residents, permanent residents, migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, overseas-born people, tauiwi ethnic minority, etc. Each of these may have legal significance depending on the statute in question. Different procedures and regulations may apply to each category.

I will not try to define all these terms here, but be aware that there can be subtle differences that matter tremendously to people in each category. The rest of this article will try to be as accurate as possible with terminology.

The general issue is that all these categories of people—some intersecting with each other—should be treated equally and fairly. So there is not just one singular detail in the current law or the proposed law to focus on, but many angles to consider. We will look at some of them, not comprehensively.

The current law

To understand the benefits and costs of the proposed law, we have to compare it to the current law. To summarise the key provisions of the status quo:

- An eligible adult or child can ask a Family Court to issue a declaration as to sex to be shown on birth certificates. This is a relatively complex procedure, and moreso for children.

- The declaration is served upon the Registrar-General of Births, Deaths and Marriages, to update the register which records births in New Zealand, and possibly New Zealand citizens-by-descent even if born overseas. It may also be served upon any other person (conceivably a foreign government).

- The Registrar-General may, after certain procedures and fees, update the register and issue a new birth certificate, if any of that is possible in a given case.

- The old information will be kept private (except in special circumstances—somewhat questionably, such as in the case of checking if a proposed marriage is “between a man and a woman”).

- The old information will be kept private (except in special circumstances—somewhat questionably, such as in the case of checking if a proposed marriage is “between a man and a woman”).

- To be “eligible” includes citizens and residents, even if born overseas, meaning that someone without a New Zealand birth certificate could initiate an application to the Family Court and win a declaration as to sex.

- Overseas-born people can conceivably take that declaration to their birthplace's jurisdiction, if it means anything, as some form of evidence. This is practically useless in most of the world, but interestingly has been used with some success at least in the UK (which recognises NZ Family Court declarations within its onerous gender recognition process).

There are clearly many problems with the current system, not least of which is the principled antagonism to self-identification built into the procedure to seek a judge's approval (to their “satisfaction”), and with complex and intimidating legal paperwork (affidavits) with medical evidence. Courts in the common law mould seem naturally opposed to self-identification, and they rather favour findings that meet burdens of proof by other evidence. It is dubious whether a court is an appropriate venue at all for any of this.

The proposed law

So it seems reasonable at first that there is a bill to amend the BDMRR Act, by introducing a standard statutory declaration procedure bypassing the Family Court, relying instead on Justices of the Peace etc., to update a sex marker.

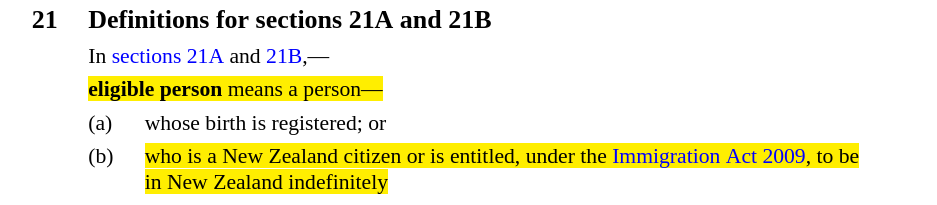

However, the proposed BDMRR Bill strikes out the definition of “eligible adult” or “eligible child” and replaces them with a narrower selection of people: only those whose births were, in the first place, registered under the BDMRR Act. That will only mean those births that took place in New Zealand.

So the tenuous procedure in the previous law to acquire a Family Court declaration and try to use it as some kind of evidence overseas, is neatly removed. What provisions take its place for overseas-born people in the proposed law, then?

None.

Racism

Having no provisions in New Zealand law to support overseas-born people changing their sex marker in New Zealand, including immigrant citizens of New Zealand, makes the new law racist because of the following argument.

Those who are from overseas jurisdictions privileged by colonisation that took away wealth, land, and culture, are likely to find relatively supportive—if embattled—governments that allow some pathway to amending their birth records and other documents (such as passports).

- These are more likely to be white-majority societies.

Those who are from other overseas jurisdictions, disadvantaged by colonisation and the hateful norms and laws inflicted by imperialists, may not be so lucky to have supportive legal regimes to amend their paperwork. More likely, they will face criminalisation and persecution.

- These are more likely to be nonwhite-majority societies.

A New Zealand law that only provides for New Zealand birth records and paperwork, can rely on overseas governments to take care of some of New Zealand's citizens and residents, belonging to the first privileged category above.

But a New Zealand law that only provides for New Zealand birth records and paperwork, cannot rely on overseas governments to take care of other citizens, residents, and refugees of New Zealand, from the second disadvantaged category above.

Predominantly nonwhite New Zealand citizens, residents, and refugees, who were born overseas, will be excluded, by virtue of colonial legacies, combined with New Zealand's current abdication of responsibility in the face of that unfortunate history (some of which it was complicit in perpetrating or exploiting).

Foreign documents not our problem?

But is it actually an abdication of New Zealand's responsibility, if the documents in question were issued overseas? Is it even reasonable to expect little New Zealand to update some foreign document? How can New Zealand be responsible for documents it did not issue?

Let us let the BDMRR Act answer that question:

The BDMRR Act permits any citizen or permanent resident to register a name change—that is, to update a key piece of information recorded in their birth certificate, even if that certificate was issued overseas.

For overseas birth certificates, this is achieved by issuing a name change certificate, rather than modifying the foreign document, and it can be used as evidence in any situation where a name is called for.

Typically, a person's assigned sex marker is recorded in the same way as a name on a birth certificate. So, at a minimum, can New Zealand not issue some kind of, say, sex marker change certificate too?

The distinction between the name change process and the sex marker change process is entirely arbitrary. It is nothing more than the policing of gender. We can already see this in how a name may be changed by statutory declaration or deed poll under the BDMRR Act.

The arbitrary distinction between name and gender properties that both come from a birth certificate—foreign or not—is maintained in the proposed BDMRR Bill, by permitting name changes by citizens and permanent residents, but not sex marker changes.

We take care of our own?

If the double standard for name changes is not a clear enough case to show it is not about which country issues a document, let us also consider the twisted tale of New Zealand's citizenship certificates.

New Zealand issues citizenship certificates. They are New Zealand documents, which record a gender marker. However, they allow applicants to select a nominated gender, which need not align with a birth certificate. How progressive.

The catch is that citizenship certificates cannot be updated—they are supposedly “point-in-time records”. Despite New Zealand issuing and controlling the document, statute does not permit updates.

Suppose there is an immigrant to New Zealand from a transphobic country, who finds it unsafe to be outed until after they become a New Zealand citizen. Suppose this person applies for a citizenship certificate, keeping all their details the same as before—to avoid the risk of being outed in the event of a failed application. Suppose, then, they succeed in their application and become a New Zealand citizen, and then seek to update their citizenship certificate. They will find they cannot do so.

What New Zealand offers, interestingly, is a second-rate “evidentiary certificate”. It is a document issued after-the-fact, to declare that a citizen's gender is other than what the citizenship certificate displays. Now that sounds awfully like our hypothetical sex marker change certificate that was comparable to a name change certificate.

So New Zealand does not even offer a pathway to amend gender on all documents it controls.

Hope for a solution

Now, we know two things from existing laws and procedures:

- It is possible for New Zealand to issue changes to overseas-recorded birth information for citizens and permanent residents at least (e.g. name change).

- It is possible for New Zealand to issue a document representing a sex marker change for citizens at least (i.e. citizenship “evidentiary certificate”).

Then it must be possible to, at least, conceive of a sex marker change certificate as a feasible option. Let us not get too far ahead of ourselves and imagine this is the only solution, but it is enough to show we can expect better than what is proposed for now.

We also know that even if New Zealand controls a document (citizenship certificate), the state takes no interest in making it possible to update sex marker. That tells us something about the motive behind the lawmaking we see, that treats not only gender and sex as a special category that is complicated to update, but also applies narrow definitions of eligibility (or, if I may: worthiness) that disadvantage overseas-born people, who will be disproportionately nonwhite and subject to colonial norms and values of transphobia or interphobia.

It is a bleak picture, but perhaps it can be rectified, given what we learned about name changes and citizenship certificates. How?

Developing policy options

Rather than proposing a single solution—although that tends to sell better—we should explore multiple options and compare benefits and costs. We can iterate on our ideas to see if any options can be improved.

One worthwhile aspiration in developing solutions should be to unify the pathways that New Zealand-born and overseas-born people need to take to update their sex marker on all records. As much as possible, there should be parity.

Option 1: sex marker change certificate

The basic option developed in the argument above is to create a new document which we have called a sex marker change certificate, that can be issued to all applicants, regardless of place of birth, as a result of a statutory declaration.

This certificate could even be used by New Zealand-born people to instruct the Registrar-General to re-issue a new birth certificate, and as evidence in rare cases where the details of a change may be necessary to prove (as an alternative that is controlled by the person, rather than a section 77 lookup in the register).

The same document could of course be issued to overseas-born people. Within New Zealand's jurisdiction, it could be used like a name change certificate is used as evidence of a changed name alongside any other identity documents. While this does not hide old information, it at least prevents the propagation of the wrong gender marker. In some ways, this hypothetical certificate parallels the UK's gender recognition certificate (GRC), but without the same onerous barrier to entry.

Option 2: identity change certificate

We can advance our hypothetical sex marker change certificate in a couple of ways. One is to unify the name change and sex marker change documents into one—after all, the latter may commonly happen at the same time as the former. So we might end up with an identity change certificate—removing emphasis on sex.

Option 3: identity certificate

Another improvement would be to statutorily recognise the new certificate as a valid substitute for an original birth certificate, making it not a change certificate, but simply an identity certificate. That means no party in New Zealand (except in some special circumstances) can reject our hypothetical identity certificate when they ask for a birth certificate. That minimises exposure to the old information in instances where it is not warranted. This is similar to the existing name change certificate in that it is effective New Zealand without updating any overseas document.

But also like a name change certificate, the identity certificate would be redundant for New Zealand-born people, because they can keep using their updated birth certificate with old information automatically hidden. As our identity certificate might no longer record the full change of details, it adds nothing to the statutory declaration for New Zealand-born people. So they can stick with a statutory declaration process, while overseas-born people use identity certificates (as happens with name change already).

Option 4: certificate of overseas birth

For overseas-born people, we could narrow the identity certificate to a substitute birth certificate: we could call it, a certificate of overseas birth. It would be based, after all, on witnessing an original birth certificate—some copy of which might be kept by the government at the time of registration.

In other words, it brings New Zealand back into the business of widely recording overseas births. Historically, New Zealand has recorded overseas births, such as for New Zealanders-by-descent, i.e. those who were born to New Zealand parents outside of New Zealand. Internal Affairs is quite capable of managing birth records with place names outside of New Zealand, per the Citizenship Regulations 2002.

We could, to provide parity for New Zealand-born and overseas-born people in New Zealand, maintain a register of overseas births, which could be automatically updated at any time a person becomes eligible. In the current law, that might be upon gaining permanent residence or citizenship—in which case, the register of persons granted citizenship could be useful.

So, with whatever register we use, our hypothetical record of overseas birth could, by law, be defined to substitute for any overseas birth certificate, through the issuing of a certificate of overseas birth. It would be effective at least within New Zealand's jurisdiction. Being a fully New Zealand-controlled document (a bit like a citizenship certificate), New Zealand could allow for it to be updated freely, perhaps by statutory declaration.

Option 5: return of the citizenship certificate

If we choose to limit documentary self-identification only to citizens, the citizenship certificate itself could take that place through new legislation that would also make it possible to amend the document directly (instead of “evidentiary certificates”).

However, to be as broad-based as possible, the certificate of overseas birth should be more freely available to non-citizens also. It could even be issued at the time of first application or arrival (as in the case of asylum seekers and refugees) for anyone intending to stay long-term.

Any such alternative regime of birth certification also has potential incidental benefits for immigrants besides the gender marker. Those who come to New Zealand from places with hostile, unstable, or dysfunctional governments, may not enjoy the security and reliability of having an important document like a birth certificate re-issued after a house fire in New Zealand, for example. A certificate of overseas birth that is maintained by New Zealand from first arrival, could be reissued more readily.

One downside is that a statutory certificate of overseas birth or identity certificate has perhaps less meaning (if not legal weight) when it comes to overriding an overseas passport (as with permanent residents), than an identity change certificate or a sex marker change certificate.

Another downside is that it relies on the government to collect more information, which is generally a privacy liability.

Unhelpful options

Return of the Family Court?

One major alternative that some people put forward is that overseas-born people might still petition the Family Court for a declaration, after the BDMRR Bill is enacted, and special provisions are removed. No special statutory provision is needed to approach a court for any cause. But this is a problem for three reasons.

First, we have shown that the current BDMRR Act makes the Family Court equally available to New Zealand-born and overseas-born people. That provision arose after a court case under the pre-2008 version BDMRR Act. The old law applied to “a person who has attained the age of 18 years” (and not any defined “eligible” person). Interpreting that law in W v Registrar-General, Births, Deaths and Marriages, Ellis DCJ reportedly found that to satisfy equal treatment under the law, an application for a declaration for an overseas-born New Zealand citizen was warranted.

So the basis for an overseas-born person to gain a declaration was that a New Zealand-born person could also enjoy that right under the law. Under today's law, courts need not apply that interpretation, because statute is clear about who is eligible—a formalisation of Ellis DCJ's ruling.

If the provision for a court declaration is removed, then we fall back to the court's discretion and interpretation of the law, and the test for equal treatment. In that scenario, because no New Zealand-born person would be entitled to a court declaration as to sex, there may be no basis to extend that right equally to overseas-born people. After all, anyone can try petitioning a court for a unicorn or a million bucks if they feel like it, but there is no reason the court has to hear it or issue a ruling in favour.

Anyway, the equal treatment principle might already be satisfied because an overseas-born person could make a statutory declaration just like a New Zealand-born person. Only it would be futile because nothing would be updated. (Similarly to the symbolic Family Court process.) That does nothing to help anyone.

Second, even if the courts do find some basis for continuing to issue declarations as to sex without a statutory provision, that means overseas-born people will be stuck with the Family Court—far from self-identifying. The premise of the BDMRR Bill is that the Family Court is antithetical to self-identification. So we would have second-class treatment for overseas-born people.

Third, the silver lining of the existing Family Court process was that it symbolically tried to account for overseas-born people too. It was never particularly effective (arguably outside the UK), but it represented a commitment in the law to be more inclusive. It opens the door to substantive improvement for overseas-born people as long as we maintain broad eligibility. The proposed BDMRR Bill is an opportunity to make exactly those improvements, in the direction set by the current symbolic provision, equally with improvements for New Zealand-born people.

Nobody wants to rely on the Family Court. Self-identification should be available to all, and it should be as effective as possible, at least within New Zealand jurisdiction. So there cannot be a return or reversion to the Family Court for overseas-born people.

Get a driver's licence or passport?

Another common view shared by the Department of Internal Affairs is that an overseas-born person could get a driver's licence or passport so that they may be able to update some useful identity document.

(Take a moment to marvel at the Department's opinion excerpted above. They claim that the BDMRR Bill has no extra-territorial jurisdiction, but the demand is for New Zealand to do something within its jurisdiction to care for overseas-born people. They claim that overseas-born people have to comply with the laws of their country of birth, knowing fully that those laws may persecute those people. They cheekily claim that a citizenship record may be updated, knowing fully that it cannot, but rather a secondary evidentiary certificate would be issued (a process they could adopt for overseas records). They then refer to “preferred gender identity”, which gives us a hint about their view on the nature of the subject more broadly.)

This approach of relying on a driver's licence or passport is fraught for three reasons.

First, the passport is subject to the same racist-transphobic context globally as a birth certificate. Temporary or permanent residents would still carry a passport from their country of origin, which may be hostile to their gender situation. That deprives them of gender self-identification within New Zealand's jurisdiction (where New Zealand law nevertheless supports name changes contrary to their passport).

Second, a requirement to have a driver's licence or passport places arbitrary barriers for overseas-born people. In the case of a driver's licence, why should updating a gender marker require knowledge of the road code? With passports, it means applying for—and gaining—citizenship, something which is out-of-reach for so many migrants such as workers and students disproportionately exploited by this country for labour and education fees, with slim chance of ever finding a pathway to citizenship.

Third, a driver's licence does not actually display a gender marker, although one is recorded in a database and used by the state bureaucracy. That means someone without citizenship (say, a permanent resident), who manages to get a driver's licence, and even updates it, will still be left without an identity document that affirms their correct gender marker and name together.

So it is still sub-standard treatment for overseas-born people to rely on existing identity documents other than their birth or citizenship information, compared to the privilege afforded to New Zealand-born people in the BDMRR Bill.

From options to recommendations?

Having explored a range of options, we can start thinking about what it would take to form a recommendation. But have we thought hard enough?

So there are clearly many options for developing a policy to amend the legislation, potentially touching not just the BDMRR Act, but also the Citizenship Act, and perhaps other laws as well.

A key difference in this approach is accounting for the needs of overseas-born people—especially those of nonwhite community members—when drafting legislation. These needs have not been canvassed thus far; not even, as far as I can tell, by select committee, Crown Law, or the other checks and balances in the legislative process.

The BDMRR Bill has instead been under attack by transphobic, interphobic bad-faith actors. The reaction by activists and allies to that pressure has been to rally around what is, frankly, a fiery dumpster of a draft law, and defend it until its passing. We need to stop this and ask serious, good-faith questions of our own instead.

The BDMRR Bill is far from fit for passage. No second or third reading will fix it. We have to return to the drawing board and actually consult rainbow ethnic minority folks to see what laws need to be drafted to accommodate all our needs to achieve maximum parity between New Zealand-born and overseas-born people while introducing self-identification.

So although we have explored a range of options above, it is impossible for one person to dictate what must become the final recommendation for you to demand from your Member of Parliament. That requires consultation and legal work beyond the scope of a blog post. That work has not been done in relation to tauiwi rainbow ethnic minority communities, and it must be done by the government. These grassroots communities are not well-organised, do not have resources or safety to be highly visible, and lack legal support to draft legislation.

Until that foundational work is done by the government, we find ourselves rallying around a racist, white-supremacist version of a law that could feasibly have been drafted equitably, but for the negligence of our supposed allies in parliament and beyond. Our allies are quick to judge “TERFs”—correctly—for being white supremacists. But what use is that, if our allies then promote legislation that is white-supremacist by omission, in our name?

Conclusion: we live in a colony

In New Zealand, we have a deeply-entrenched view that rainbow issues do not intersect with racial or ethnic diversity. This false assumption manifests in exclusionary laws like the BDMRR Bill. But it also rears its head in other laws like a proposed conversion therapy ban that would rely on the racist-transphobic-homophobic-misogynist-classist nexus of police, courts, prisons, and the immigration system, to punitively surveil and monitor already over-policed racial minorities in the name of protecting LGBT+ rights. Both of these legislative strategies are fundamentally rooted in a settler-colonial Pākehā mindset.

We have to understand that legislation does not sit in a vacuum. Governments led by Labour or National have both, for decades, persisted with xenophobic racism in policy-making. It was a Labour government that undermined jus soli birthright citizenship, in fear of Asian anchor babies nearly twenty years ago. It is a Labour government today that is scapegoating migrant workers for allegedly depressing wages and squeezing the housing market. We are not exempt from this brutal onslaught when a centre-left government is in power. There remains a legal fence even between real citizens and citizens-by-grant. Proposed laws like the BDMRR Bill (and the Prohibition of Conversion Therapy Bill) should be considered in this context: the continuing proscription of full, foreign lives.

We have to do better than that.